INFORMATION

Feminism And The Chicano Movement

"The issue of equality, freedom, and self-determination of the Chicana- like the right of self-determination, equality, and liberation of the Mexican Chicano community- is not negotiable."

-Francisca Flores

The First National Chicana Rights Conference

The first National Chicana Rights Conference took place in Houston, Texas, during May of 1971. Organized by Elma Barrera, the event consisted of about six hundred Mexican-American women who discussed free abortions, birth control, sex education, and the issue of misogyny within both the Mexican-American community and Chicano movement.

On the third day of the conference, almost half of the women demonstrated a walkout- their goal being to make the statement that Chicanas should not fight for their rights as women, but as Hispanics. This demonstration shows how the support of women's rights fluctuated within the community; however, the conference remained influential in the progression of the conversation surrounding feminism. The very gathering of six hundred Chicanas shows the sharp turn the community was taking, especialy considering that it was declared during the Chicano Youth Liberation Conference that " the Chicana woman does not yet want to be liberated" just two years prior.

Dolores Huerta

Dolores Huerta dedicated her early career to fighting for the labor rights of Hispanics in the United States, specificaly migrant workers in California grape farms. Alongside activist Cesar Chavez, she co-founded the National Farmworkers Association (NFA), a union for migrant farmworkers. Much of the credit for their work went to Chavez, with Huerta having to work in his shadow. In 1965, the NFA merged with the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee, forming the United Farmworkers of America (UFA). It was at this time she and Chavez led a three-thousand-person labor strike against California grape farms. After nearly five years of labor strikes and a national boycott of California grapes, many farms began to sign contracts with the union for better working conditions for their migrant workers.

Given her status as one of the few prominent female activists in the movement, Huerta took it into her own hands to advocate for issues such as sexual harassment, childcare, and gender equality policy within labor unions. This path led her to speak at the National Organization of Women and alongside 3000 other female union members Huerta co-founded the Coalition of Labor Union Women (CLUW). The CLUW is for all women, regardless of race, age or orentation. The establishment of this Union represents how progress can only be made when different groups band together despite their differences, and is a turning point for the relationship between Hispanic and white women.

The CLUW still exists today, standing as the only national organization union for women. The union flights for equal pay, childcare, contraceptive equality, affordable healthcare and protections against sexual harassment in the workplace.

Throughout the rest of her career as an activist, Huerta became a voice for the LGBTQ community, the poor, women, immigrants, and families. Today, she holds the Presidential Medal of Freedom and is founder and president of the Dolores Huerta Foundation.

Francisca Flores

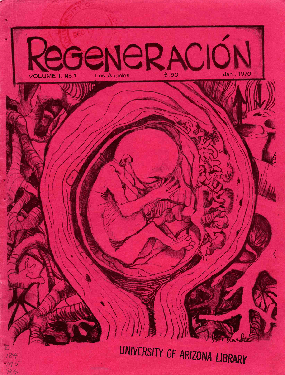

Regeneración 1, no. 1, January 1970, Special Collections, The University of Arizona

Francisca Flores' work was pivotal in the expansion of Latina voices in the political sphere. She founded the Hermanas de la Revolución Mexicana, an organization that gave women a space to voice their opinions on politics and activism in both the United States and Mexico.

Flores would go on to become a prominent journalist during the time of the Chicano movement, writing for La Luz, Mas Grafica and Regeneración. In an issue of Regeneración she famously wrote that, "The issue of equality, freedom, and self-determination of the Chicana- like the right of self-determination, equality, and liberation of the Mexican Chicano community- is not negotiable." Her assertive tone in her writing was unique for her time and caught the eye of many, including the FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover, who called her a "most dangerous individual."

Flores also founded and was president of the Comisión Femenil Mexicana Nacional (CFMN)- the first national Chicana organization in the United States. The third resolution of the establishing document reads, "In order to terminate exclusion of female leadership in the Chicano/Mexican movement and in the community, be it RESOLVED that a Chicana/Mexican Women's Commission be established at this conference which will represent women, in all areas where Mexicans prevail" The establishment of the CFMN was pivotal in the creation of the separate feminist movement for Chicanas. The organization established up bi-lingual learning centers for chidren of immigrants, gave job recources to Latinas and trained women in leadership- adressing many of the issues that Chicanas uniquely faced surrounding childcare and employment. The CFMN still exists today, with its most notable chapter being located in the San Fernando Valley, where community organizers and volunteers work to provide scholarships, career opportunities and networking opportunities to young latinas.

Martha Cotera

Martha Cotera is a Librarian, author, and activist who wrote for the Chicano movement and the Chicana feminist movement. In the height of the Chicano movement, she and her husband founded a political party in Texas known as La Raza Unidada (LRU). The main goal of the party was to elect Mexican- Americans into Texan political offices. The party had a handfull of local politial successes, including a majority on the Crystal City, Texas, school board and city counicl. This majority allowed them to instill a bilingual program for students in the district and promote the hiring of Mexican-Americans.

During the time of La Raza Unidada, Cotera began to push for feminism in the party. She famoulsy said, "if you're working for liberation, you can't do it by gender. It's a liberation for all." This statement was met with harsh criticism from men within the movement, but Cotera never stopped. Inorder to give women the space to prosper in politics she, alongside other women in the LRU founded the Mujeres de La Raza Unida, which primarily focused on uplifting Latinas in politics, educating women in Texas on activism and blending feminism with the Chicano movement.

After the movement began to simmer, she would go on to publish two of her most influential pieces: Diosa y Hembra: The History and Heritage of Chicanas in the U.S. and The Chicana Feminist. Diosa y Hembra provides a consensus of the general history of Chicanas, unearthing forgotten stories and pushing back against the stereotypes that many Latinas were pushed into at the time which were primarily being labled as pushovers and less than their male counterparts. The books inspired many young Mexican-American women to keep the movement alive and brought many of the issues Chicanas faced into mainstream media.

Her other book, The Chicana Feminist is a collection of speeches and essays by Cotera that reflect on and critique the Chicano movement and broader feminist movement. In it, she calls out the sexism and rejection of female leads exhibited by the actions male leaders took during the movement. She also comments on the racism Hispanic women faced from white feminists. The books tone can be humorus at times, allowing it to be more approachable to audiences that may have never considered the Chicana view before, and gives current readers a first-hand look into the past.